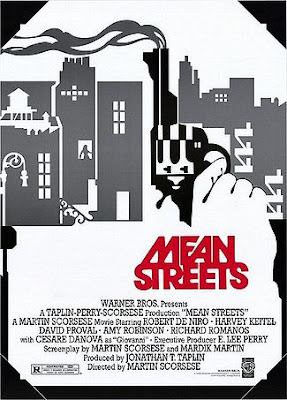

Over the years, I've seen a lot of movies... A LOT of movies. Some have been decent, most terrible, and a few good. But a handful have been truly thought provoking, mentally stimulating works of art. Martin Scorsese's 1973 feature, "Mean Streets" is one of those. Aside from being one of my favorite films, "Mean Streets" is a confluence of talents, style, writing, and production that serve as a benchmark in the medium.

Originally titled "Season of the Witch", Mean Streets was written over the course of several years by Martin Scorsese and Mardik Martin. Like its precursor film, "Who's that Knocking at My Door", Mean Streets is somewhat a documentary about a young Scorsese, the Lower Manhattan neighborhood he grew-up in, and ultimately working-class neighborhoods in general.

After making his first budget-film, "Boxcar Bertha" (1971) for B-Movie producer, Roger Corman, Scorsese was encouraged to do a project close to his heart... a labor of love. Corman initially offered to finance the film, but only on the condition that the entire cast be black. At a time when films like "Super Fly" and "Coffey" were major box-office earners, the King of Exploitation's offer was not as outlandish at it might seem, nor was the fact the Scorsese considered it. Ultimately, Scorsese turned-down the offer and "Mean Streets" was made on a budget of roughly $500,000, a paltry sum for a film, even in the early 1970's.

"Mean Streets" revolves around Charlie Cappa (played brilliantly by Harvey Keitel), a Little Italy local and protege of his Mafia Capo uncle, Giovanni (played by Cesare Danova). His life consists of collecting debts for his uncle, hanging-out at "Volpe's" a gin mill owned by his friend, Tony (played by David Proval), keeping his friend "Johnny Boy" Civello (played by Robert DeNiro) out of trouble, obsessing over a black stripper (Jeannie Bell), and carrying-on a clandestine affair with Johnny Boy's cousin, Teresa (Amy Robinson).

The conflict in the story is within Charlie himself. A devoutly Roman Catholic, Charlie fears the hell he knows surely awaits him, even to the point of masochistic self-inflicted pain. As a collector for his uncle, Charlie is promised ownership of a restaurant. The only problem, Charlie's gain will come at the cost of another man's debt to Giovanni. Charlie's Catholic guilt creates a compulsion in him to "save" others. One of those Charlie dedicates himself to "saving" is the volatile and possibly unhinged Johnny Boy who owes money all around, but most importantly to the wolfish and stone-like loan shark, Michael (played by Richard Romanus). Along with his taboo love affair with the epileptic Teresa, Charlie finds himself torn between loyalty to his friend, his lover, his career and his faith.

"Mean Streets" is not a simple story; it is reflective, gritty, uncompromising, dark, humorous, touching and heartbreaking. From the beginning, the audience is immersed in this story, these characters, this time, this place and its emotion. Martin Scorsese, showing the colors of an early master, introduces us to the time, place and characters using quick vignettes and by rolling fake Super 8 home movies over the opening credits. It looks authentic, it sounds authentic, it feels authentic. Scorsese creates a reality for us to invest in.

Scorsese's mobsters may be dressed nice, and even a bit of fun, but they are fundamentally petty, volatile and bleak. They are everything that movie mobsters aren't supposed to be... they're real. Scorsese's New York City isn't the romantic wonderland of "Manhattan" or the shining Oz of many films. The New York City Mean Streets inhabits is the NYC of the 1970's, the real deal. Grimy, graffitied, garish and garbage-strewn. Sex in Mean Streets is not romantic or lofty; it's funky, awkward and beautifully human. Violence in Mean Streets is not dramatic or epic; it's split-second and unsettling. War veterans are on edge, squeegee men wait at traffic lights, raucous parties rage in tenement apartments. No Sinatra, this is Rolling Stones territory. Mean Streets is the reaction to the Godfather.

Somehow, in all this sleaze and violence and urban disorder, Scorsese makes the audience feel right at home. It seems normal enough, even mundane. From the chaos of the San Gennaro Feast, to the crimson-soaked Saturday night at the bar, to the Italian eateries, the tenement apartments, building air shafts, the sub-level pool hall, the dark streets of the Lower East Side, the Churchyard, even the the rooftops; none of it feels like a movie. The dialogue is so real, so fast, so hard and so natural that it's hard to believe that any of it was ever scripted. The characters so natural, so unbalanced and so organic that the viewer gets fooled into believing that they're real people. The conflict and the tension is so palpable and relatable that the viewer finds him or her self becoming emotionally invested at times. The brawls, the arguments, the profanity-laced conversations are all a given. They fail to shock an audience that develops a normalcy and relationship with the story and its players.

The film, like virtually all of Martin Scorsese's pictures, is scored wall-to-wall with contemporary music. From pop to rock to Italian folk songs, one gets the impression that Scorsese designed the film's soundtrack from his own record collection. A fact that he has admitted it in several interviews. Now, scoring a film with popular music is tricky. In fact, in most films, one can argue that it doesn't generally work well. The tone of a song may match that of a scene, but the meaning of the song may not. Or, conversely, the lyrics may relate to the film, but the tone of the song itself can kill the mood of a scene. More often-than-not, however, it just comes-off as hackneyed and lazy. In Mean Streets, the music created the mood. It worked. Without fail.

The costumes of Mean Streets are too often overlooked. Though not truly "costumes", the clothes worn by our cast of low-brow Bowery boys are defined by the characters wearing them. Conflicted Charlie, is clad in the double-breasted, pin-striped suits of an Italian gangster when placating his uncle. Yet, he wears neutral-tones of beige and green when trying to defend Johnny Boy or soul searching with Teresa. Johnny Boy is the image of chaos in his leather jacket and mismatched get-ups. Tony, entirely in red, matches the sleazy danger of his saloon. Micheal in black, grey and white. Like stone, ice cold. Richard Romanus seems almost born to play that role, his face looks almost carved from granite; threatening even when splattered with cake.

Mean Streets is very much a film of its time. It reflects the 1970's. Its mood, its style, its subject matter. Martin Scorsese was of that generation inspired by the "New Wave" of European cinema in the previous decades. And that naturalism and cinematography certainly shows in Mean Streets. But Scorsese was also highly influenced by the gangster films of his youth. And that too shows, even in Charlie's pinstriped suits. In a way Mean Streets is very much an heir to the Pre-Code gangster pictures of Cagney and Muni. Mean Streets is as much "Little Caesar" as it is "Le Mepris".

Now, to be fair, which I will, Mean Streets did have some problems. As good as its plot was, Mean Streets seems to take side trips that, although well executed, lead nowhere. Scorsese introduces characters or seems to begin exploring ideas in the film that never get expanded-on or tied-up. Almost like random happenings in the movie's world. They just seem to happen for no real reason and in the end, Charlie has learned nothing from them, and neither have we. Just padding. These foibles, however, do not detract from the overall picture and are certainly not regrettable.

Mean Streets launched multiple careers and indeed changed the way films were conceptualized and executed. A product of an artistically open time, when being different was prized and being subversive was exulted, Mean Streets defined one generation and inspired another. It certainly inspires moi. For anyone who fancies themselves as a cinemaphile, Seeing "Mean Streets" isn't just recommended, it's required.

No squirrels scurried, no birds sang, no stray cat searched-out a meal in the trash bin. She took slow, labored steps, looking to the ground and the shimmer of light on her boots. She hoped for someone, anyone to walk her way, to cross her path, to acknowledge her presence.

No squirrels scurried, no birds sang, no stray cat searched-out a meal in the trash bin. She took slow, labored steps, looking to the ground and the shimmer of light on her boots. She hoped for someone, anyone to walk her way, to cross her path, to acknowledge her presence.